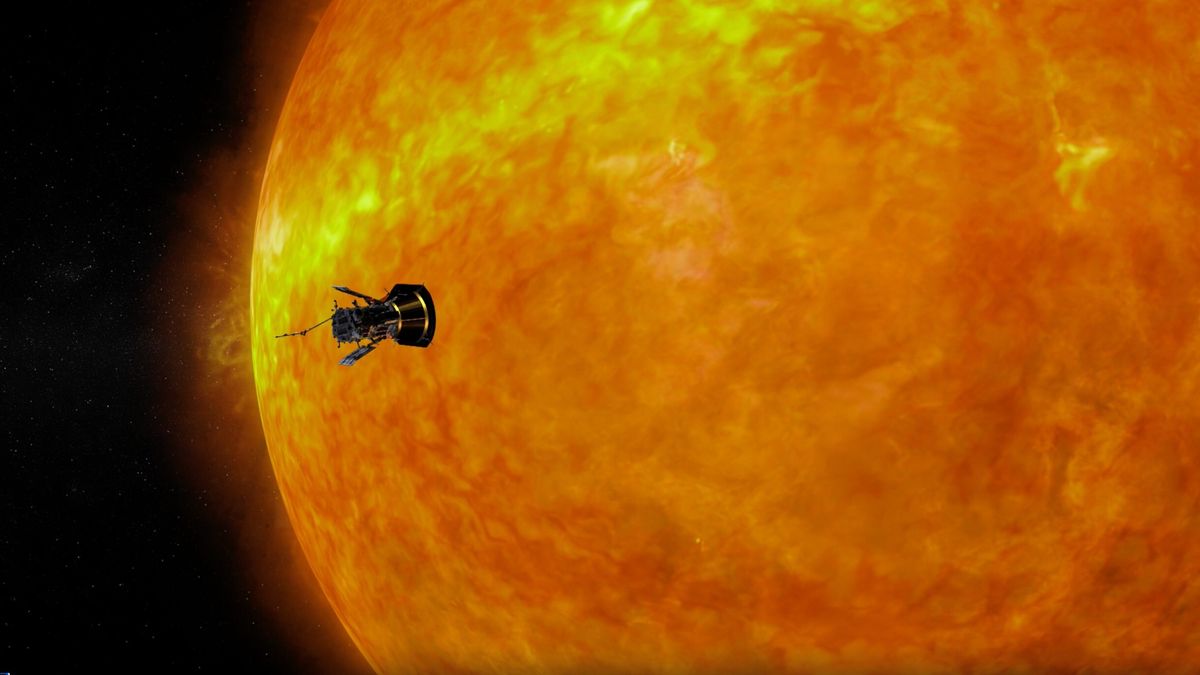

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe is spending Christmas Eve on a history-making attempt to fly closer to the sun than we have ever been before — a stunning technological feat that scientists liken to the historic Apollo moon landing in 1969.

At 6:53 a.m. ET on Tuesday (Dec. 24), the car-sized spacecraft was scheduled to zoom within 3.8 million miles (6.1 million kilometers) of the sun’s surface, nearly 10 times closer than Mercury’s orbit around the star. The probe was traveling at an incredible speed of 430,000 mph (690,000 kph) — fast enough to travel from Tokyo to Washington, D.C. in less than a minute — breaking its own record as the fastest human-made object in history.

“Right now, Parker Solar Probe has achieved what we designed the mission for,” Nicola Fox, the associate administrator for NASA Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., said in a NASA video released on Dec. 24. “It’s just a total ‘Yay! We did it’ moment.”

Mission control cannot communicate with the probe during this rendezvous due to its vicinity to the sun, and will only know how the spacecraft fared in the early hours of Dec. 27 after a beacon signal confirms both the flyby’s success and the overall state of the spacecraft. Images gathered during the flyby will beam home in early January, followed by scientific data later in the month when the probe swoops further away from the sun, Nour Rawafi, who is the project scientist for the mission, told reporters at the Annual Meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) earlier this month.

Related: 10 supercharged solar storms that blew us away in 2024

“We can’t wait to receive that first status update from the spacecraft and start receiving the science data in the coming weeks,” Arik Posner, the program scientist for the Parker Solar Probe at NASA Headquarters, said in a statement.

“No human-made object has ever passed this close to a star, so Parker will truly be returning data from uncharted territory,” added Nick Pinkine, the Parker Solar Probe mission operations manager at the Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland.

HAPPENING RIGHT NOW: NASA’s Parker Solar Probe is making its closest-ever approach to the Sun! 🛰️ ☀️ More on this historic moment from @NASAScienceAA Nicola Fox 👇 Follow Parker’s journey: https://t.co/MtDPCEK6w6#3point8 pic.twitter.com/Bq85XFa1QSDecember 24, 2024

Parker launched in 2018 to help decode some of the biggest mysteries about our sun, such as why its outermost layer, the corona, heats up as it moves further from the sun’s surface, and what processes accelerate charged particles to near-light speeds. In addition to revolutionizing our understanding about the sun, the probe also caught rare closeups of passing comets and studied the surface of Venus.

On Christmas Eve, scientists expect the probe to have flown through plumes of plasma still attached to the sun, and hope it observed solar flares occurring simultaneously due to ramped-up turbulence on the sun’s surface, which spark breathtaking auroras on Earth but also disrupt communication systems and other technology.

“The sun is doing different things than it did when we first launched,” Nicholeen Viall, who is a co-investigator for the WISPR instrument onboard Parker Solar Probe, told reporters at the AGU meeting. “That is really cool because it is making different types of solar winds and solar storms.”

Parker’s 4.5-inch-thick heat shield is designed to endure temperatures of up to 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit (1,371 degrees Celsius), partly thanks to a specially-designed white coating that will reflect much of the sun’s heat and help maintain spacecraft instruments at a comfortable room temperature.

But scientists expect Parker to witness lower temperatures of about 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit (982 degrees Celsius), Elizabeth Congdon, the lead engineer for the probe’s thermal protection system, told reporters at AGU.

“It’s really great to see all the science that is enabled by the fact that we overprepared.”