Inflammation can reawaken dormant viruses in the brain, which may help to explain why concussions often precede dementia, a new study finds.

Brain injuries like concussions raise the risk of dementia, and the more blows someone takes to the head, the higher that risk becomes, evidence suggests. Scientists are investigating what happens in the brain after injury that might lead to changes tied to dementia — for instance, a buildup of abnormal proteins and the malfunction and death of brain cells. Such changes are seen in Alzheimer’s disease and chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a disorder that’s recently gained recognition in high-impact sports.

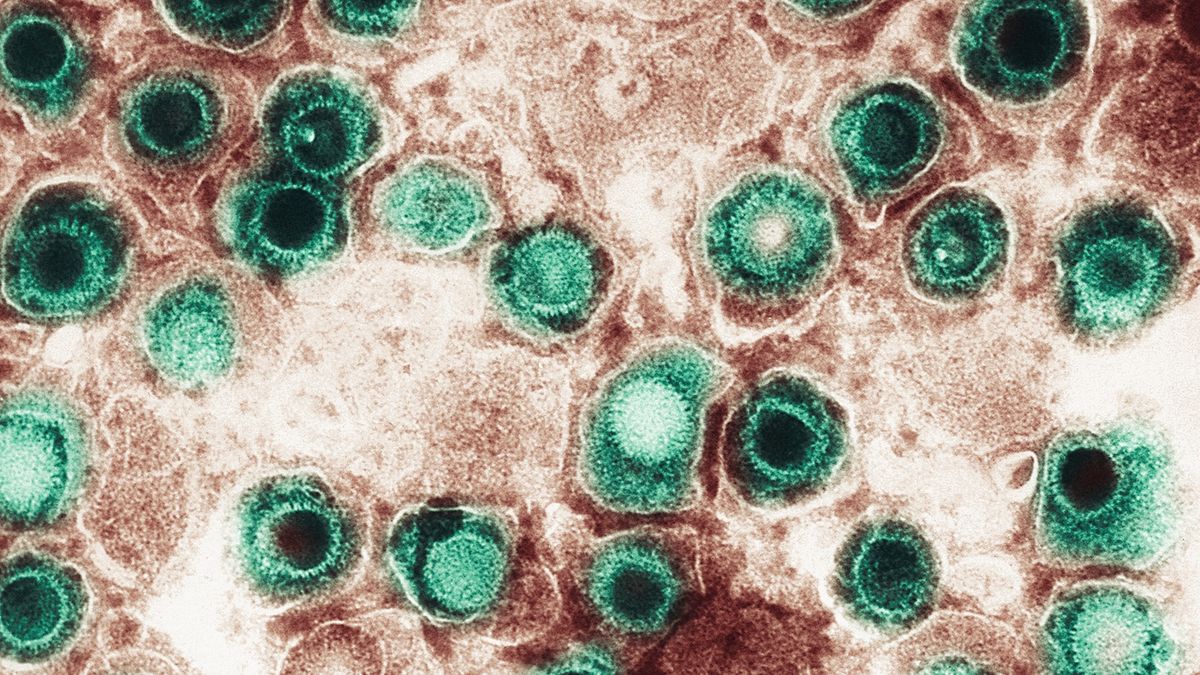

Some scientists think these changes may be linked to a common virus: herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1), the germ behind cold sores.

Herpesviruses — a broader group that also includes the viruses behind chickenpox and mono — have an ability to go dormant in the body and then later reactivate. “They can remain latent in your body forever,” said lead study author Dana Cairns, a postdoctoral research fellow at Tufts University. There’s evidence that HSV-1 can somehow weasel its way into the brain and then lie there in wait, Cairns told Live Science.

Related: Lab-grown ‘minibrains’ help reveal why traumatic brain injury raises dementia risk

What’s new here is that the researchers have demonstrated that physical injury can activate latent viruses in the brain, said Dr. Gorazd Stokin, who leads a neuroscience lab at the Institute of Molecular and Translational Medicine in the Czech Republic and was not involved in the new study.

The new research relied on miniature laboratory models of the brain, so more work will be needed to show that the results are relevant to people. “But it’s a good first step to show something interesting,” said Stokin, who is also a consultant neurologist at the Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust in the U.K.

Viruses in dementia

The idea of viruses sparking dementia isn’t new; Ruth Itzhaki, a co-author of the new paper, raised the notion in 1991. Itzhaki and colleagues had found the virus in the brains of older adults who had died of Alzheimer’s. They later found that people who carry both the virus and ApoE4 — a gene variant that raises Alzheimer’s risk — have a higher risk of the disease than those with ApoE4 alone. They also found that latent HSV-1 can be reawakened by stress or immunosuppression.

“In those days, she got a lot of pushback,” Cairns said of Itzhaki’s early work. This viral theory of dementia remained niche for decades, but in recent years, interest has increased. Nowadays, scientists also have better tools to test the theory, including lab-grown models of the human brain.

The new research, published Tuesday (Jan. 7) in the journal Science Advances, used brain models measuring only 0.2 inches (6 millimeters) across. The spongy, doughnut-shaped structures are made of silk and imbued with stem cells. With specific chemicals, the stem cells are made to mature into various brain cells that carry one copy of ApoE4. This genetic trait is “relatively common” among people with Alzheimer’s, Stokin noted, so it’s relevant to include in a brain model.

The researchers infected these models with HSV-1 and then pushed the virus into dormancy with an antiviral drug. In past research, they had shown that inflammation could “wake up” the virus and that this triggered brain-cell changes also seen in dementia. In that previous work, the researchers triggered the inflammation with varicella-zoster virus, the virus behind chickenpox and shingles.

But “there are other things besides infection that cause inflammation, like injury,” Cairns said. “We wanted to understand if maybe injury could be doing something similar.”

In the new study, the team subjected the minibrains to models of two types of injury: severe injury, as if the skull had broken open, and concussions, in which the brain moves or twists in the skull. In the concussion experiments, the minibrains were placed in 3D-printed containers filled with fluid, similar to the fluid that cushions the brain inside the skull. The encased minibrains were then put on a platform that was struck with a piston.

In both experiments, the brain models became inflamed and the HSV-1 in them reactivated. Dementia-related changes, like an accumulation of proteins, showed up in these infected brain models, but not in injured-but-uninfected models that were used for comparison.

The severe-injury experiment damaged the cells so badly that they soon died, but the cells in the concussion experiment survived and thus the experiment could be repeated. The more times it was repeated, the worse the dementia-like pathology of the infected models became.

“The people that are exposed to more chronic injuries over time often clinically have the worst manifestations of neurodegeneration,” Cairns noted. “It [the experiment] really correlated very well with that concept.”

Additional experiments by the team hinted that blocking inflammation after injury could help stop HSV-1 from reactivating and thus prevent the signs of dementia from arising. This finding strengthened the team’s overall results, Stokin said. However, because the results have been shown in only minibrains, “trying to do the same in animal models would be useful,” he added.

The researchers plan to continue experimenting with their brain models to see what might stop HSV-1 from reawakening — for instance, anti-inflammatory or antiviral drugs may work, Cairns said.

“If you can block reactivation, or somehow control the viral load … that would be beneficial,” Stokin said, assuming herpes truly is a missing link between brain injury and dementia.