Archaeologists in the Iberian Peninsula have discovered a 65,000-year-old tar-making “factory” engineered by Neanderthals — a feat pulled off 20,000 years before modern humans (Homo sapiens) set foot in the region, a new study finds.

The sticky tar helped Neanderthals produce glue to make weapons and tools. The so-called factory — a carefully designed hearth — enabled the Neanderthals to precisely control the fire and manage the temperature of the flame that produced their gooey creations.

Archaeologists already knew that Neanderthals made glue, including tar and resin as well as sticky substances from ochre, a reddish mineral often used for rock art. Neanderthals used these sticky materials to haft, or attach, stone blades or points to wooden handles, in combination with sinew or plant fiber wrappings.

But the newfound hearth, seemingly dug into the floor of a cave in what is now Gibraltar, shows that Neanderthals were skilled engineers who had fine-tuned the glue-making process.

“The structure that has revealed a hitherto unknown way by which Neanderthals managed and used fire,” the researchers wrote in the new study, published Nov. 12 in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews.

Related: Did we kill the Neanderthals? New research may finally answer an age-old question.

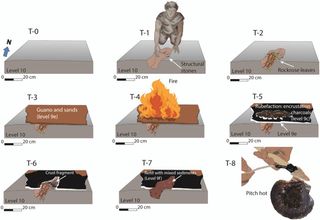

The Neanderthal hearth looks deceptively simple at first glance: It’s a round pit, nearly 9 inches across by 3.5 inches deep (22 by 9 centimeters), with sharply cut vertical walls. Two short trenches about an inch long extend north and south of the pit. But if the researchers are correct, it’s a feat of precision engineering.

Neanderthal technology in the Stone Age

Inside of the hearth, the team found traces of charcoal and partially burned rockrose, a flowering shrub; small crystalline lumps of cooled plant resin; and thin twigs from local shrubs. They analyzed samples taken from the blackened walls and floor of the hearth with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, which identifies the individual chemicals in a sample of material. This revealed traces of urea and zinc from guano (bird or bat poop), chemicals associated with burning, and remnants from the protective wax on plant leaves.

The findings resembled one of the experimental ways another group of researchers produced Paleolithic tar in 2017. That earlier study suggested a hearth — really more of a buried oven — like this one would have been perfect for heating certain plants to distill tar or resin for hafting tools.

To make these so-called glue factories, Neanderthals likely filled the pit with leaves from nearby rockrose plants, which produce a sticky, dark brown resin when heated, the researchers of the new study wrote. Next, they covered the pit with a layer of wet sand and soil, probably mixed with guano to help seal the inside of the pit and keep oxygen out, which would have prevented any flames from burning the contents to a crisp. Finally, they built a small fire on top using thin twigs, which would heat the rockrose leaves in the chamber below.

Every step of the process, and every feature of the hearth itself, was carefully planned, the team said. It’s easier to control the temperature of a fire made of thin twigs, and the Neanderthals using the hearth would have needed to heat the rockrose leaves to around 300 degrees Fahrenheit (150 degrees Celsius), but not much hotter. And they needed to keep oxygen away from the leaves in the pit, because too much oxygen would let the resin burn up instead of melting.

To investigate this method, Ochando and his colleagues built their own replica of the kiln, producing enough resin to haft two spear points. It took them about four hours from the time they started collecting rockrose leaves to the time they finished hafting their spear points — they even managed to knap the spear points from local flint while the rockrose leaves were heating. Once the leaves were heated, the archaeologists squeezed the melted resin out of the leaves into shells from the nearby beach.

In the process, Ochando and his colleagues discovered that producing resin may have been a two-person job.

“Our colleagues noticed during the experimental archaeology experience that they need to manage the fire covering the plant and also open the crust [the covering over the kiln],” study co-author Francisco Jiménez-Espejo, a scientist at the Andalusian Earth Sciences Institute, told Live Science in an email. He suggested that the two straight channels on either side of the pit might have marked where two Neanderthals dug into the pit, from opposite sides, to remove the heated leaves before they cooled. That’s because it’s difficult to “separate the tar” from cooled leaves, he said.

If Neanderthals really worked this way, they weren’t just good engineers, they were good at teamwork, too.