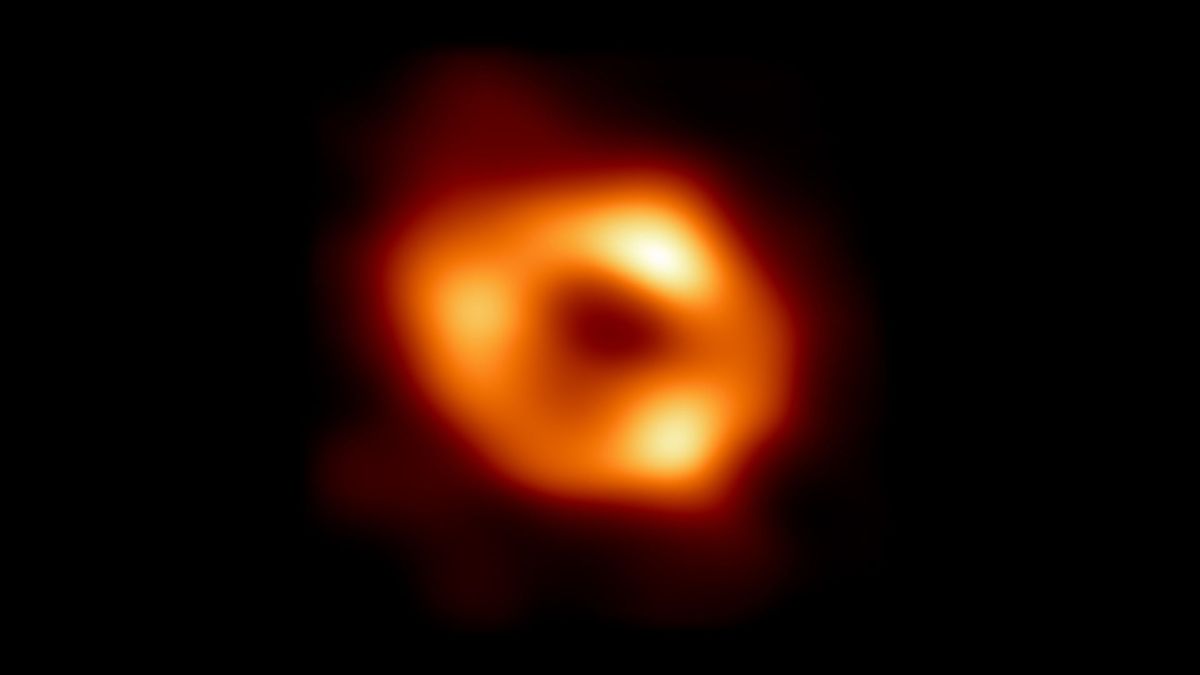

The first ever image of the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way may not be as accurate as it initially seemed, a new study claims.

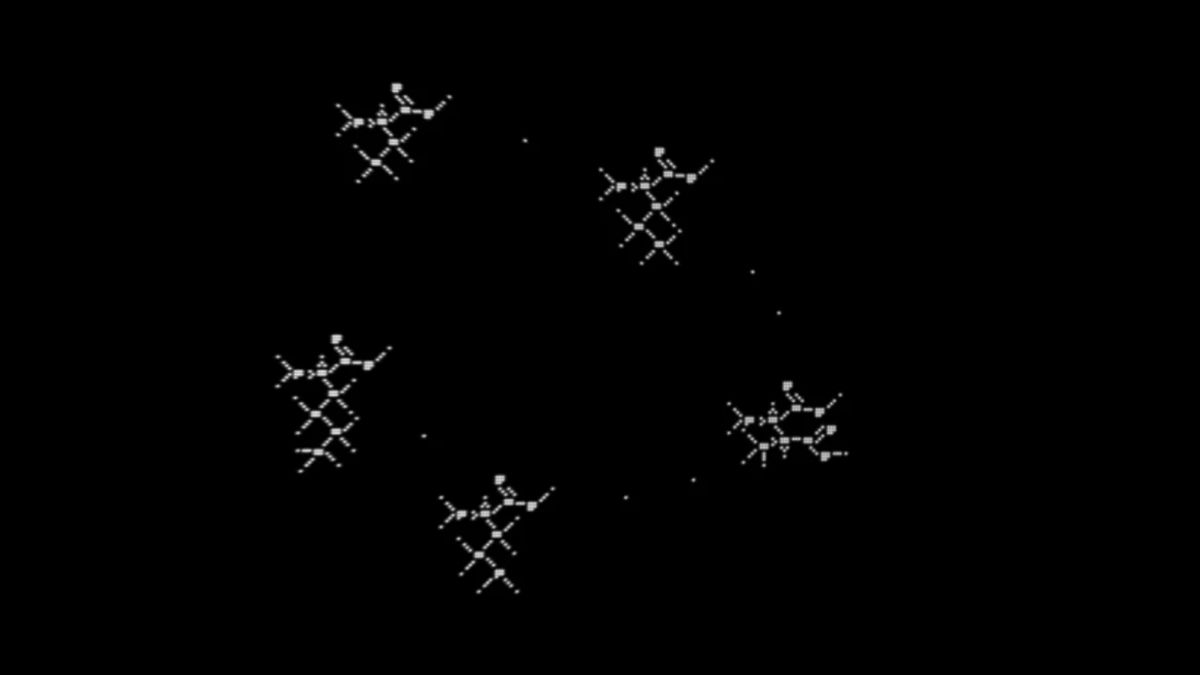

Located 26,000 light-years from Earth, Sagittarius A* is a gargantuan tear in space-time that is 4.3 million times the mass of our sun. The groundbreaking image of the black hole, which was released in 2022, was captured by the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), a network of eight synchronized radio telescopes located in various spots around the world.

But the orange, doughnut-shaped ring of gas surrounding the galaxy could be distorted due to the way the data was stitched together. According to new research, published in the November issue of Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, the ring is actually more elongated than it appears in the famous image.

“Our [revised] image is slightly elongated in the east-west direction, and the eastern half is brighter than the western half,” study lead author Miyoshi Makoto, an astronomer at the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ), said in a statement. “We hypothesize that the ring image resulted from errors during EHT’s imaging analysis and that part of it was an artifact, rather than the actual astronomical structure.”

Related: Accidental discovery of 1st-ever ‘black hole triple’ system challenges what we know about how singularities form

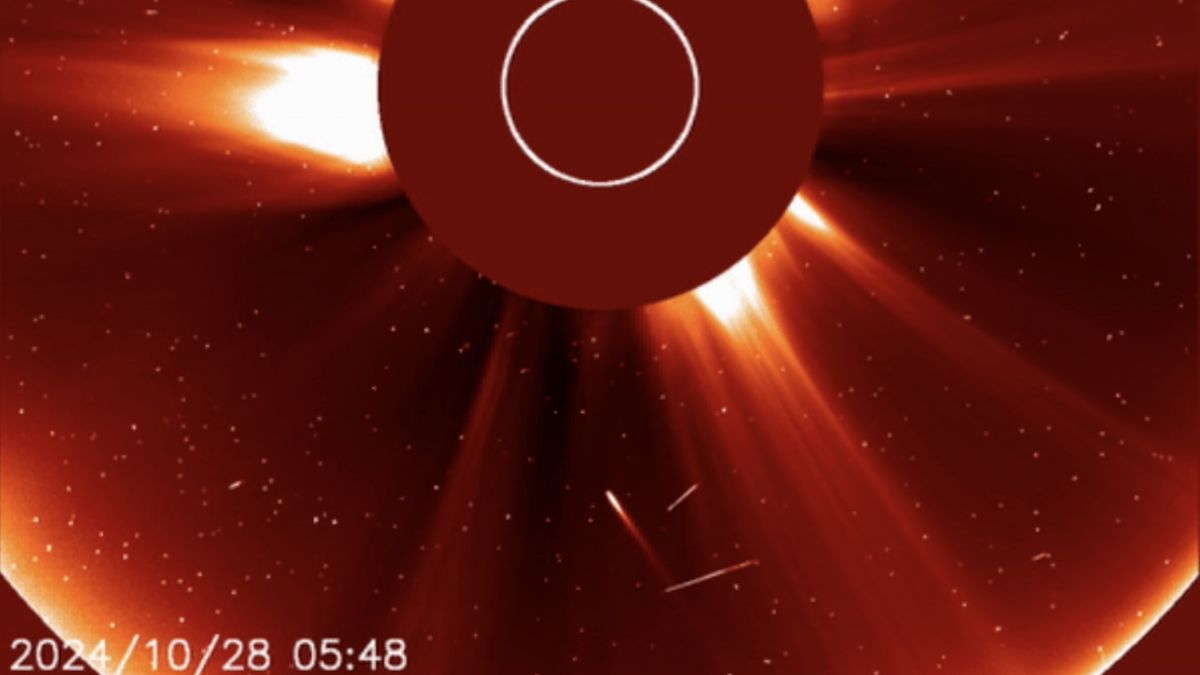

The EHT captured the image, as well as an image of the supermassive black hole at the center of the M87 galaxy, in 2017. The image of the M87 black hole was released in 2019, but it took two more years of data analysis before the Milky Way one was ready.

The imaging process was time-consuming for a number of reasons. Firstly, plasma whips around the black hole’s accretion disk at a remarkable speed, taking mere minutes to make a complete orbit. Earth’s location at the edge of the Milky Way also meant the researchers had to use a supercomputer to filter out interference from the huge number of stars, gas and dust clouds strewn between our planet and Sagittarius A*.

To capture the image, the EHT took readings from its radio telescopes dotted around the globe, then stitched the data together to construct the final image. But this puzzle piece approach could have left noticeable gaps in the data.

To check the image, the NAOJ astronomers applied what they called “widely-used traditional” analysis methods, producing results that showed the disk was more squished along its central axis than it appeared in the original image.

The EHT team has yet to comment on the new findings, and it remains unclear which view of the disk is the most accurate. The researchers behind the new study hope their findings will provoke a healthy discussion from which a more reliable picture of our galaxy’s giant black hole will emerge.