Like many children, I had a natural curiosity for the living world from a young age. My childhood was filled with bug-hunting, pond-dipping and watching David Attenborough documentaries. As a young adult, the books I read on biology and evolution became a bridge between my childhood curiosity and my adult obsession. I’m fortunate that my career allows me to indulge in my long-standing passion.

Having earned an undergraduate degree from the University of Edinburgh and a DPhil in evolutionary biology from the University of Oxford, I am now a professor of microbial ecology and evolution at the University of Bath in the U.K., where my lab uses an approach called experimental evolution, which allows the observation of evolution in real-time using microbes. Very broadly, we are interested in the patterns and processes that shape life’s resilience and innovations and study these by tracking the fate of mutations within a population, as determined by natural selection, within bacterial populations.

Tiffany Taylor

Tiffany Taylor is a professor of Microbial Ecology and Evolution at the University of Bath in the U.K., where her research group studies evolution in real-time in the lab, using bacteria. She has also authored three children’s books on evolution and genetics.

While I consider myself an evolutionary biologist, over time I began to appreciate microbes not just as tools for studying evolution but for their fascinating biology, for their essential role in the health of humans and the planet, and for the unassuming beauty they possess when observed closely. Both these threads — evolution and microbes — continue to be central to my research today.

Related: Best science books for kids and young adults

There are many excellent science books that offer a gateway into the fascinating fields of evolution and microbiology. Here are my top five reads that have, in some way, changed my personal or scientific perceptions of the world.

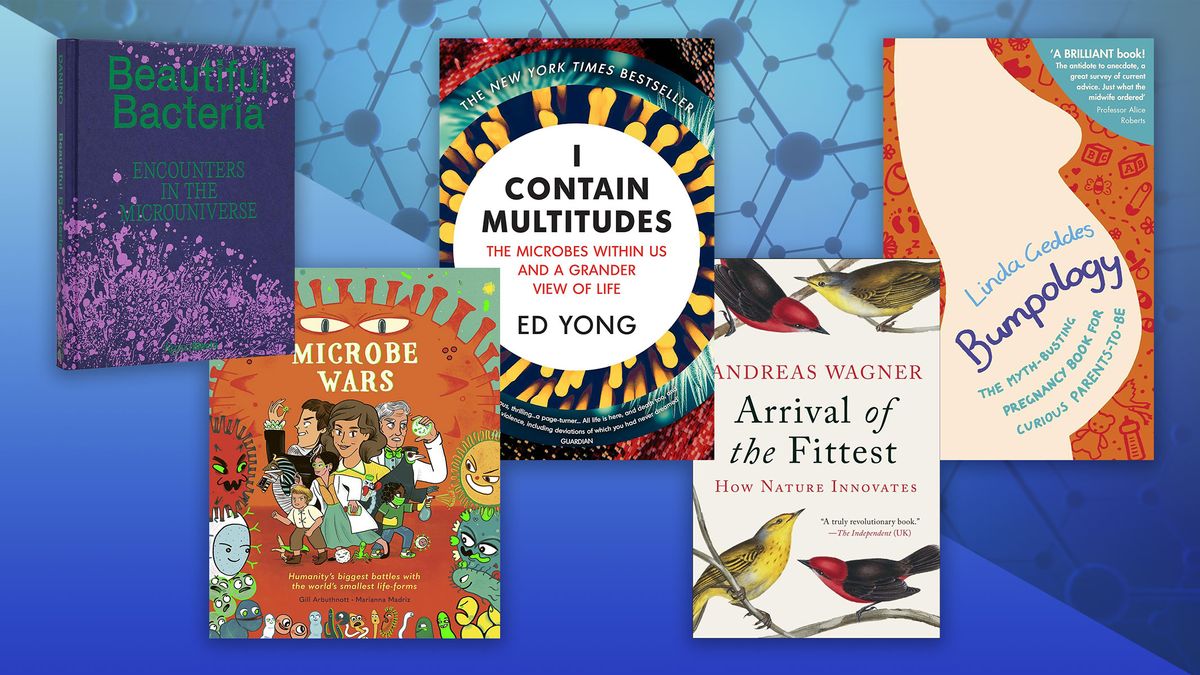

The first book I recommend is “Beautiful Bacteria: Encounters in the Microuniverse” by Tal Danino.

Danino’s research involves engineering glowing bacteria that form distinctive, rhythmic patterns of fluorescent proteins as they move across the plate. Recognising the beauty in his work, his book showcases visually stunning photographs of bacteria that blur the lines between art and science. I find myself equally amazed by and curious about the underlying processes that can create such beauty.

My own research also involves looking at bacteria that swim across the plate. My first experiment with bacteria involved counting green and white colonies on an agar plate — a dish filled with a jelly-like food source on which you can grow bacteria. The green ones excreted a protein that helped them scavenge the iron they needed to grow when iron was scarce (like in the human body), while the white ones had a mutation preventing this. I loved coming to the lab in the morning and seeing these different microbial hues, it gave the bacteria character somehow, and it made me appreciate that bacteria had an aesthetic appeal, as well a practical one. Danino’s book reminds me of this, and to stop and wonder at the patterns as well as the process when I can.

Another book that looks at the tiny microbes I spend all day in the lab with is “I Contain Multitudes: The Microbes Within Us and a Grander View of Life” by Pulitzer Prize winner Ed Yong. I spend a lot of time trying to convince people that bacteria are fascinating and worth understanding, and in his New York Times bestseller, Yong masterfully uses rich, vivid descriptions to bring microscopic worlds to life. He explores hidden ecosystems that exist in and on every living thing and delves into the lives of the researchers studying them.

This book underscores the importance of effective science communication and its power when done well

The impact of microbes cannot be underestimated: They have a profound impact on our environment and health and are responsible for driving the evolution of complex life. Our microbiomes, the bacteria that live in and on our bodies which at least equal and may exceed the number of human cells, are in constant flux, adapting to and interacting with our environments. Yong leaves us with the message that understanding and nurturing these microbial communities can benefit us all. This book underscores the importance of effective science communication and its power when done well.

Much of my work explores the origins of new genes with new functions. Andreas Wagner’s book “Arrival of the Fittest: How Nature Innovates” shaped many of my early ideas when I was setting up my lab. Taking inspiration from Charles Darwin’s seminal work on evolution, he seeks to understand not the survival but the arrival of the fittest. Where does the variation on which natural selection acts come from?

Wagner begins at life’s possible starting point — a deep-sea vent, where interacting chemical molecules changed into something we recognise as life. He challenges the notion that random mutations alone account for life’s diversity, highlighting the vastness of sequence space — the universal library of all proteins that have and could be created. For example, in a small protein with only 100 amino acids, the number of permutations to explore is greater than a 1 with 130 zeros trailing behind.

Wagner illustrates that only a fraction of this space needs exploration to find significant innovations, transforming our understanding of randomness in life’s evolutionary journey.

Books for kids and about them

Away from the world of bacteria and evolution, another one of my passions is children’s’ literature. In 2022, I sat on the panel of the Royal Society’s Young People’s Book Prize, which promotes literacy in young people and inspires them to read about science. “Microbe Wars” was my favorite among those shortlisted.

Arbuthnott and Madriz deliver a captivating introduction to the microscopic world in an engaging and accessible manner for young readers. They use humor and storytelling to convey scientific concepts and highlight the people and history behind microbiological discoveries. It fills me with joy that my children can learn how we owe vaccines to milkmaids who were seemingly protected from smallpox, or how epidemics like the Black Death have shaped human history. Best of all, this knowledge sparks their curiosity, leading to lively discussions about the exciting discoveries we’re making in my lab.

And finally, while not related to my research, the book “Bumpology: The Myth-Busting Pregnancy Book for Curious Parents-To-Be” has been important as my role as both a scientist and a parent. Balancing parenthood and a career is a tough challenge — I’ve spoken openly about the importance of ensuring that motherhood doesn’t feel incompatible with a scientific career, and I strive to support parents navigating this difficult period.

As a scientist, I thrive on data, relying on evidence and careful analysis rather than assumptions. Pregnancy and parenting, however, are often surrounded by anecdotes and old wives’ tales. Don’t get me wrong, I too have tried to exactly replicate a successful sleep routine after a rare good night’s sleep. But science isn’t about assumptions — it’s about data.

Geddes exploits the skills developed in her previous role as a journalist for New Scientist, and leverages the latest research of the time to bust myths and provide evidence-based answers to common questions about pregnancy and early infancy. This book is packed with scientifically-backed advice and fascinating insights you might never have thought to ask about.